Born: April 13, 1743

Born: April 13, 1743

Birthplace: Albemarle County, VA.

Education: College of William and Mary

Married: Martha Wayles Skelton

Occupation: Lawyer, Planter

Age at Signing: 33

Died: July 4, 1826. Age, 83.

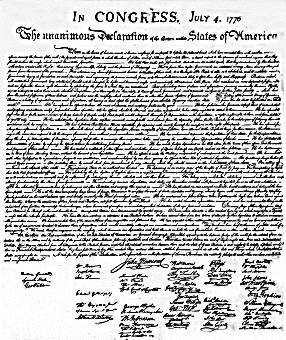

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), author of the Declaration of Independence. He was one of the most brilliant individuals in history. His interests were boundless, and his accomplishments were great and varied. He was a philosopher, educator, naturalist, politician, scientist, architect, inventor, pioneer in scientific farming, musician, and writer, and he was the foremost spokesman for democracy of his day.

Life

Born into a distinguished Virginia family, Jefferson was graduated from the college of William and Mary, and studied law under George Wythe. He practiced law from 1767 to 1774 and during these years was also a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1772 he married a beautiful and wealthy young widow, Martha Wayles Skelton. Martha Jefferson died in 1782. The death of his wife had a profound effect on Jefferson and probably influenced his return to politics.

Virginia Burgess

By the time of his marriage, Jefferson had for several years been a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. This was the lower chamber of the Virginia legislature, which was called the General Assembly. He was elected in 1768 and took his seat at Williamsburg in the spring of 1769. As a burgess, Jefferson took an active part in the events that led to the American Revolution (1775-1783). He belonged to the so-called radical group that was in opposition to the conservative planters of the Tidewater region. Many of his democratic views came from his experience as a resident of the western part of the colony, near the frontier, where he saw the colonists carve a civilization out of the wilderness. This strengthened his lifelong belief that people could and should govern themselves.

Jefferson was a poor speaker, but his literary talents made him a highly valued member of committees when resolutions and other public papers were drafted.

Townshend Acts

In 1769 Jefferson joined his fellow burgesses in opposing the Townshend Acts. These laws passed by the British Parliament required the colonies to pay duties on paint, lead, paper, and tea. They also made changes in colonial administration that turbed the colonists. The Massachusetts legislature appealed to the other colonies for concerted action against the laws. Virginia responded with resolutions protesting the acts. Governor Botetourt, learning of the resolutions, dissolved the General Assembly. However, the burgesses moved their meeting to the Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg, where Jefferson and the others signed an association, or pledge of action. Drafted by Burgess George Mason and introduced by Burgess George Washington, the document went far beyond any previous protest. It bound its signers not to buy a number of imported goods until the Townshend duties were abolished. Faced with the prospect of a boycott, Great Britain lifted most of the offensive duties.

Committee of Correspondence

In 1773, in retaliation for the burning of the British ship Gaspée near Providence, Rhode Island, the British government ordered a special court of inquiry and threatened to send the perpetrators to Britain for trial. Jefferson and his brother-in-law Dabney Carr were among the burgesses who protested the British threats. They met secretly with burgesses Patrick Henry and Richard Henry Lee and a few others to consider a plan of action. Carr drew up a set of resolutions proposing a committee of correspondence for Virginia. The committee was to keep in touch with other colonies on matters of common interest. Other resolutions challenged the legality of the court of inquiry and protested the threat “to transmit persons accused of offenses committed in America to places beyond the seas to be tried.” The resolutions were passed by the General Assembly. Although the committee of correspondence did not include Jefferson or other so-called radicals, the first step had been taken toward communication and joint action on grievances by all the colonies.

Richmond Convention

In March 1775 Jefferson was a delegate to a Virginia convention held at Richmond to approve the decisions made at the First Continental Congress, an assembly of representatives from the different colonies that had met the previous fall to organize resistance to Britain. At Richmond it was decided that the colonies must resort to arms against England. Patrick Henry on this occasion made his stirring “give me liberty or give me death” speech. Jefferson supported Henry's call to arms with his first public address. The convention then chose him as an alternate delegate to the Second Continental Congress to serve if the elected delegate, Peyton Randolph, should be unable to attend.

Burgesses' Last Session

Before the Second Continental Congress convened, events in Virginia reached a crisis. Lord Dunmore, the governor, had angered Virginians by his high-handed conduct. They were further aroused when word came of the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, when Massachusetts militias first took up arms against the British troops. The American Revolution had begun. Dunmore was frightened and called a meeting of the General Assembly, which both Jefferson and Randolph attended.

At first, Dunmore tried to calm the assembly with assurances that no more taxes would be levied. Instead, he said, they would return to the old system whereby the colonies voluntarily contributed money to Great Britain. However, these assurances came too late to appease the Virginians. Dunmore felt his life was endangered and fled to a British warship. He never returned to Virginia.

The assembly continued to work without him. Jefferson's written reply to the assurances made by Dunmore stated that “the British Parliament has no right to intermeddle with the support of civil Government in the Colonies.” Virginia, Jefferson declared, was now represented in the Continental Congress and would go along with the decisions of the other colonies. His reply, slightly amended, was adopted by the assembly, and Jefferson left for Philadelphia and the meeting of the Continental Congress. Randolph remained in Williamsburg to preside over the assembly.